I loved bar mitzvah season, all the bar mitzvah swag... Some bar mitzvahs cost more than my wedding probably will; I remember one dance floor was basically an aquarium with fish swimming in it – poor fish. There is no one standard bar mitzvah but mine certainly wasn’t like all my friends’ bar mitzvahs. First of all, it was 3 months after my 13th birthday, and it was at an orthodox synagogue with just my extended family and the regulars. My actual birthday party was the big “hurrah” for me and my friends.

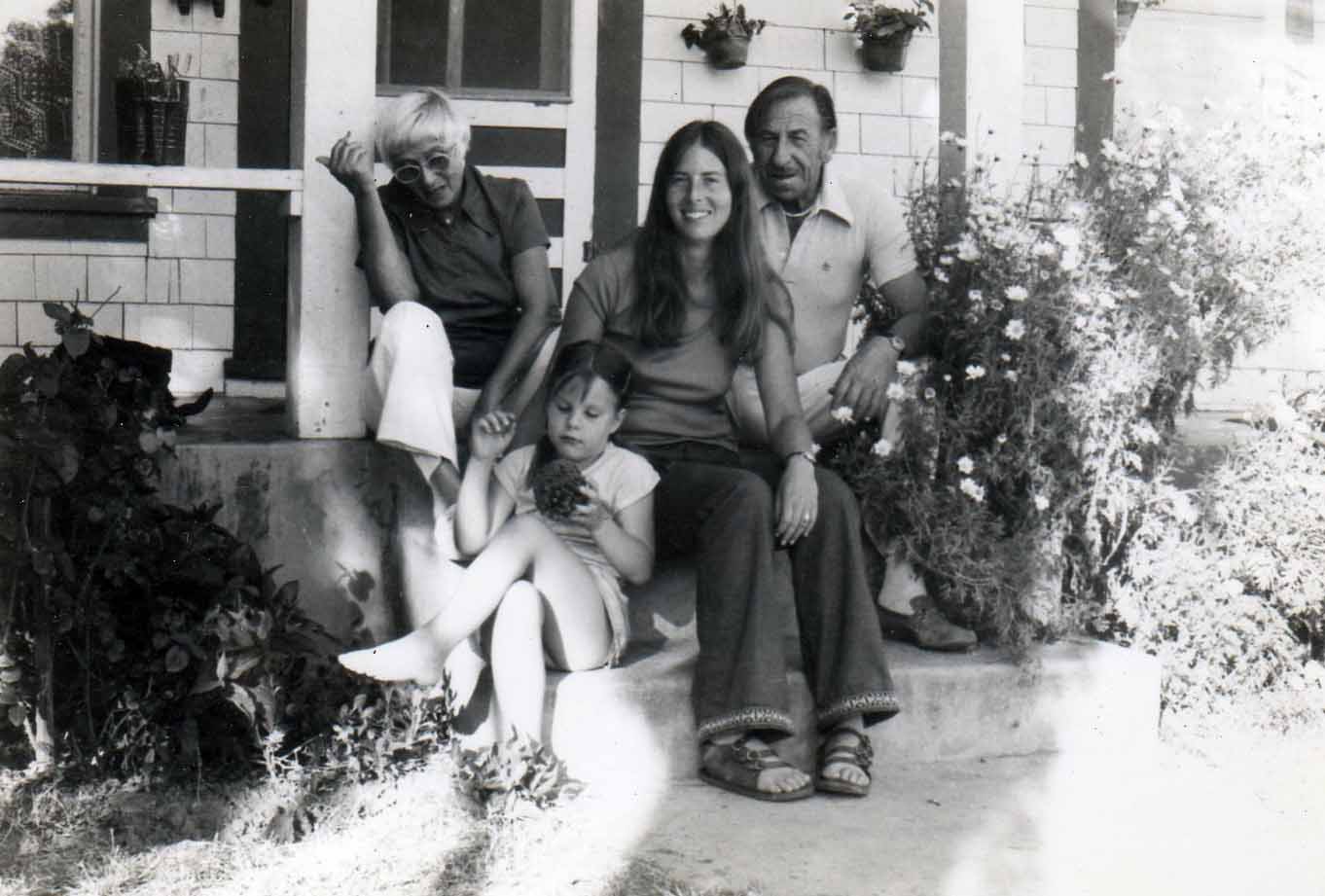

To explain why my bar mitzvah was a bit different I have to go back at least one generation. In the Soviet Union, Judaism (and all religion for that matter) was explicitly banned. My mom told me a story about how as part of her “girl scouts” duties, they were forced to stand in front of a church (another group stood in front of a synagogue) and literally stop people from entering. The communists called religion: “the drug of the masses” and saw it as a threat to their power over human behavior. Under communist philosophy, religion was equal to drug addiction, so soviet Jews were forced to go through high profile “mitzvah deals” to keep the 5000+ year old traditions going. My dad literally had to go through back-alley deals to get “the goods,”a.k.a. matzah, for Passover; pieces of thin, dry, crumbling bread were suddenly on the same level as the most addictive of drugs.

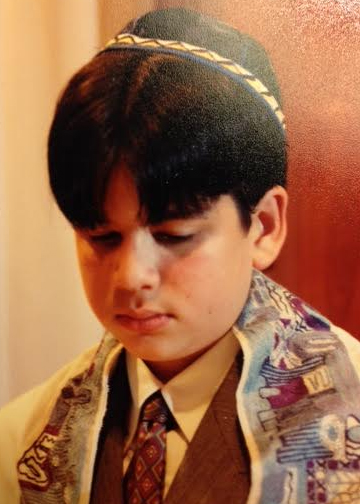

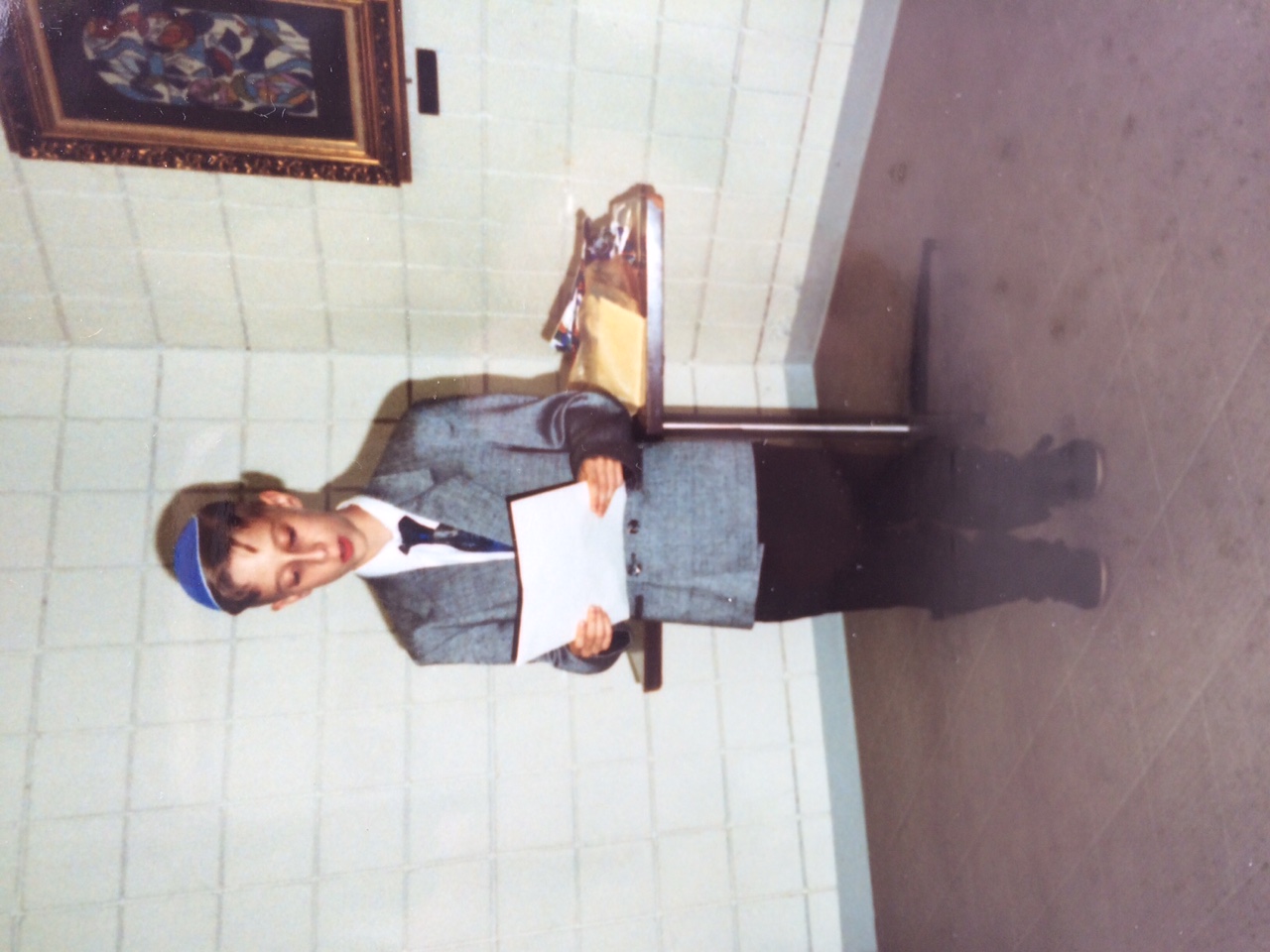

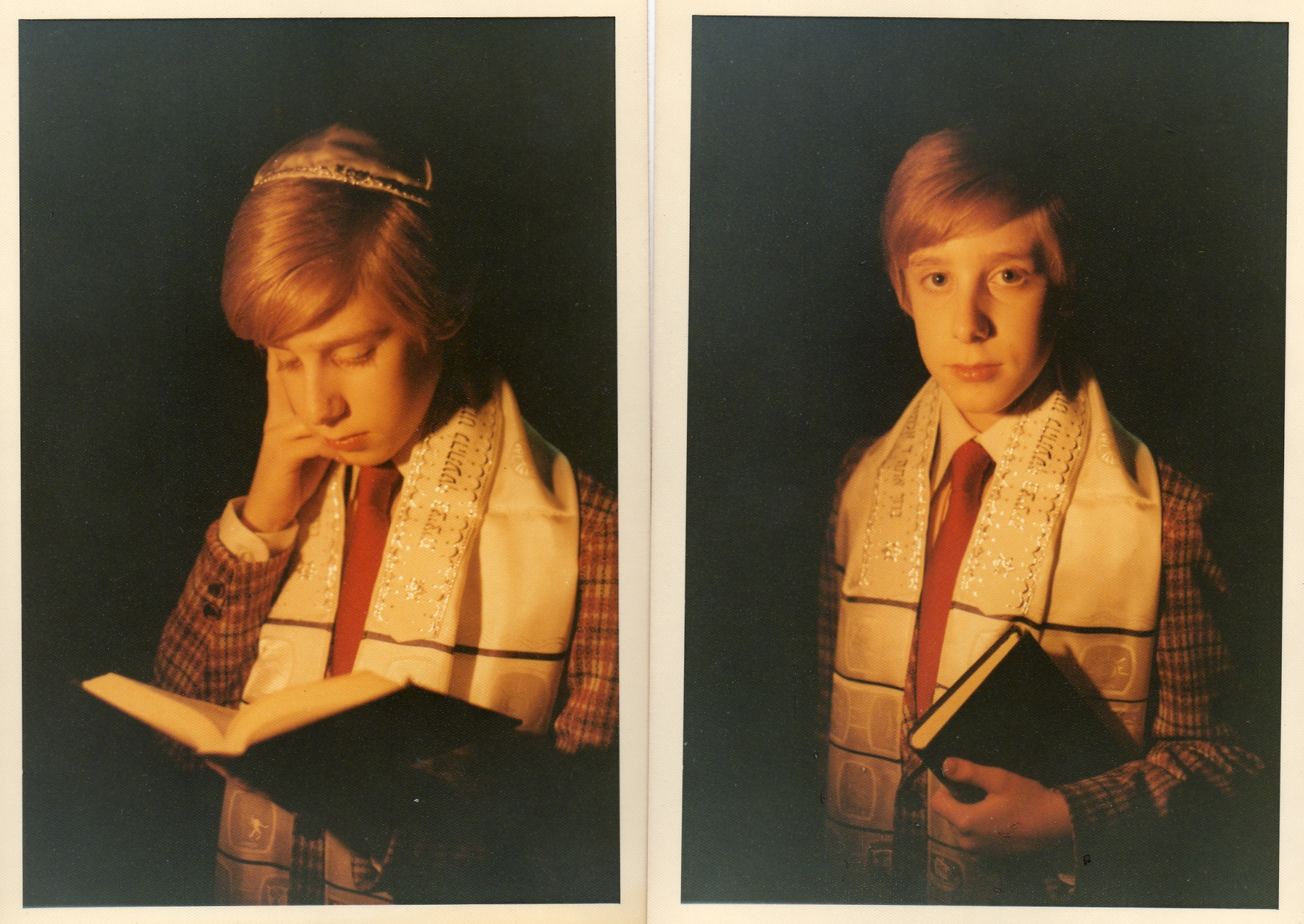

So, fast forward to Los Angeles; I’m a 12-year-old boy and my dad had just begun going to synagogue every now and then. He brought me to Shabbat one time, and the rabbi comes up to me and tells me, “it is time.” I thought, “alright… I guess I’m spending every Sunday in a synagogue for the next year.” At first I was a bit hesitant; I vaguely remember that all the other boys there were biblical scholars with mini-beards. However, the rabbi there was very inspirational, and I started enjoying the classes on Jewish history, holidays, and the cool, swirly Hebrew letters that were transformed into the vibrations of air molecules through mystical melodies. As my bar mitzvah was coming up I remember getting a tape with my haftorah portion on it, and I’m aging myself because I literally got a tape. Some of you may not know what that is, the little rectangles that go into a boom-box; the cantor basically made me a mixtape. How romantic. I remember playing that tape on repeat for months; I was like a little Eminem getting ready for my freestyle battle that was Shabbat, and I was ready to bust out that Hebrew freestyle no problem. If only I knew what it actually meant… Although in a way this made the experience more mystical, more personal because I could interpret the Hebrew in anyway I chose.

As a 13.25-year-old I led an orthodox congregation full of regulars on Shabbat, but I didn’t return to that synagogue often after my bar mitzvah, just on the major Jewish holidays. During a Yom Kippur in my late-teens I realized that I was the first in as long as anyone in my family could remember to have religious freedom – the freedom to connect with my ancestors through the exact words and rituals that they performed. With this realization, I’ve been trying to dig and see what I can find in this beautiful history of the Jewish people. I’m fascinated by the idea of the literary and ritual seeds passed down from generation to generation to flourish in the unique soil of each generation’s experience. I’ve vacillated with respect to how much I believe all the biblical stories to be literally true, but that complexity is part of the beauty of our journeys.

To finish up, I want to bring attention to our journeys here tonight.

Tying my story back to the holiday we’re celebrating today, if I had to summarize Purim in one sentence it’d be a story of how the Persian Jews managed to escape annihilation. Most of us have heard a family story just two or three generations removed from us about narrowly escaping the holocaust, pogroms in Russia, or the pogroms in the middle east and north Africa that are often over-looked. I’m not saying this to dwell on the past, but rather to draw your attention to the actual miracle that whether you’re Jewish or not, somehow through the winding and seemingly random life paths across cities, states, and continents we all made it here tonight, to this room to celebrate this holiday full of revelry. This is what my bar mitzvah now means to me: the beginning a journey of awareness and appreciation of life that will never end. With that, I say cheers!