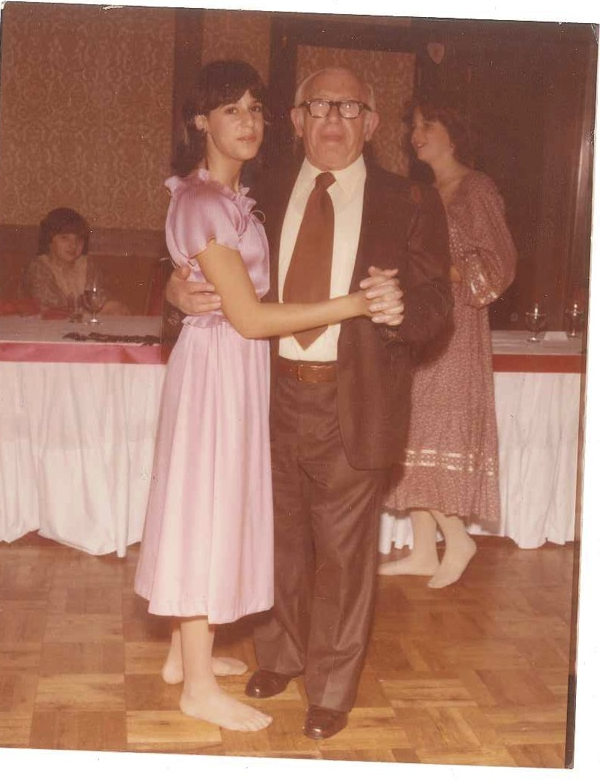

In the barefoot photo, I am dancing with my grandfather, Charles Wald.

I know B Mitzvah’s are supposed to be the stuff of becoming an adult in a spiritual way, but I will always associate my own ritual celebration with an earthier version of adulthood, one involving the open display of painted female toes. In a phrase, my Bat Mitzvah marked not merely the first time I recited Torah from the bimah, but also my inaugural experience of wearing (what I then called) “open-toe shoes.” Such shoes offered, to my mind, access to the exciting but also terrifying world of grown-up women, fully initiated into the rituals of adult sexuality, including rituals of male seduction.

While my mauve (and quite cute, I thought) Bat Mitzvah dress had been purchased well in advance of the occasion, and had been pre-approved by my mother and modeled for my grandmothers, the shoes were part of a frantic, last-minute errand I conducted, incongruously, with my father. Why my father got involved with the buying of his adolescent daughter’s shoes is lost to memory. Maybe my mother had grown weary of taking me to the girls’ sections of department-store shoe salons and having me reject everything as too prim, even as the “ladies” sections beckoned with shoes that had too much heel or too much vamp. Maybe she and I had run out of energy in figuring out what color of shoe would complement my verging-on-dusty-pink frock. What matters is this: We had less than 24 hours before the event, and I still had no shoes, and we had exhausted all of the most obvious retail options. We may even have assayed Lord & Taylor, considered by my mother to be the ne plus ultra of Philadelphia department stores.

Somehow, then, I ended up with my father in the shoe department at K-Mart the evening before the big event. I had already painted my toenails an acceptable shade of taupe, noting with some revulsion that my big toes, like other parts of my body, had sprouted telltale hairs. After having searched for appropriate shoes at Wanamaker’s and Gimbels and Sears, as well as every “young miss” specialty store for miles, I was prepared for disappointment: Perhaps I would just wear my clogs to my bat mitzvah and hope that no one noticed? But I also felt confident, secure enough in my middle-classness to know that at K-Mart I had nothing to lose, since my father was unlikely to reject a potential choice as “too expensive for a 13-year-old.”

It was there, among the faux-leather loafers and Mary Janes that I found the perfect pair of maroon (not black or brown) strappy shoes, with a sensible (no more than 2-inches), square heel and with faux (or maybe it was real) suede and patent detailing. They may well have been on sale, which would have considerably sweetened the deal for my father, who had trouble resisting a bargain, even if it was in Girls’ Shoes rather than Household Tools. If I recall accurately, we even bought an alternate pair of shoes (returnable with receipt), something more along the lines of woefully babyish Mary Janes, in case my mother disapproved. She did not.

More than three decades later, I feel a great tenderness toward the wearer of those shoes, as she performed both her Torah and Haftorah portions (along with extra readings, because she was that kind of kid), kissed multiple rouged cheeks of her mother’s happy friends (wiping off the stray lipstick stains), and disco-danced her way into a tenuous adulthood (complete with painted toenails). She already possessed plenty of self-consciousness about middle-ness, class- and otherwise. She knew what it meant, in the hierarchies of the larger Philadelphia Reform Jewish world in which she had learned about Jewishness and identity, to be somewhere in between K-Mart and Lord & Taylor. She knew that the shoes, on the borderline of “cute” and “sexy,” would pass the muster of parents themselves ambivalent and unsure about their daughter’s sexuality and a developing femininity to which, despite their authority, they had little access. She herself intuited the pleasures and dangers of adult female sexuality, liberated from the need for parental sanction. And she knew, despite the assurances of the rabbi and Jewish law, that the rituals of Judaism did not make her an adult, not even close. But that was okay, because as much as she enjoyed that day and those shoes—which, it goes without saying, she never wore again—she was also content in those clogs, the toenail polish chipping off her adolescent toes.

Gayle Wald is a writer and Professor of English at George Washington University.