There are my Grandmother’s relics that I remember most. Her uniquely African-carved walking cane. Her worn, yet cherished bible. And her ring―which included all eight of her children’s birthstones.

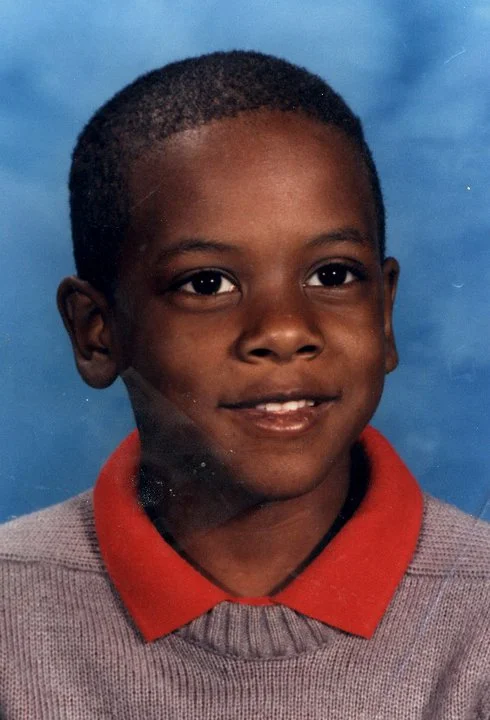

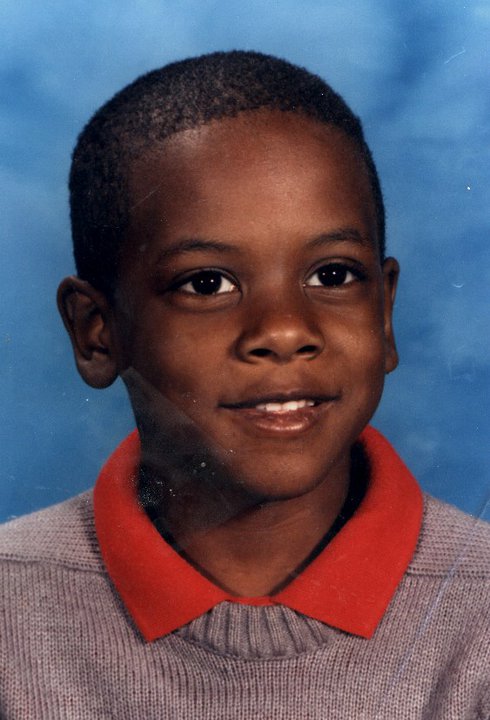

She was crazy about me―but I played grandson really well. I was well behaved, quite inquisitive, and her sisters called me “thin man,” which I hated … but I did have these big curious brown eyes.

She was thankful for me and, she never failed to remind me that as a newborn child, I was fragile and sickly―but I was a fighter.

As a preteen―in the midst of my parents’ divorcing―I found solace in transforming my Grandmother’s guestroom into my own physical space of stability. With space again to dream—and disconnect from the chaos of watching my parents disembody the pillars of our core family—I found in my grandmother, someone I could believe in, listen to, and bounce-off the ideas shaping my value system … she was there; there when it really matters. And she was perfect.

In between afternoons of Price-Is-Rice and Supermarket Showdown and evenings of bible studies and Nintendo; She taught me how to not just cook, but how to REALLY make a meal that was worthy of celebration.

See, my parents’ divorce coincided with the most vulnerable age of an adult-in-formation’s journey. I remember feeling like an intruder, as my parents essentially checked-out of parenting.

In retrospect, they were both two 30-somethings, self-determining that they needed two separate paths. It’s only natural, for a child, to get lost in that moment. Grandma was a pretty good consolation prize. An angel in disguise; Honest, giving, full of joy, and most importantly—present.

Yet, I would only have her for 13 years. As a child in the 1980s, I was well aware of my country’s history. Life was unkind to my ancestors and the collateral damage was much more present than the progress we’ve made.

Heaven was a sought-after-dream for lives filled with racism, pain, struggle, then-accepted domestic violence, and “holding on until everything would be alright.” Death could not be taken personally; it was the only glory that seemed sustainable.

With my grandmother’s death, I honestly felt that the adult in my life left the room. As we prepared to celebrate her life, in her obituary, my family included a simple hallmark poem.

In reading it, I didn’t believe the poem captured her life. Yet, these simple lines were aimed at defining her. I saw her story lost in a reflection that captured just a small part of who she was, and who we were, and thus, who I was.

From that moment, I questioned every story and whether we were properly capturing people’s lives in the words and reflections we wrote about them. I wanted to study stories and media and understand the power within. Autobiographies, music, news media, literature, and poetry … the fascination meshed well with my inquisitiveness.

From that experience, I started to write … I wanted to do my small part to better capture life. I started to share the stories of my classmates with my classmates; I begun using the poetry of my community to build a community. In my own journey—in real time—I wanted to extract the universal emotions that were left unsaid … As a pre-teen, that was quite different behavior. But, it allowed me to find a purpose in a moment where fear of the unknown was the prevailing norm.

Writing gave me discipline and reason. It gave my empty spirit a soul. It became my ladder, not just for an escape from the short-term realities I faced … where it’s easy to feel trapped in an invisible community … but ammunition to empower myself.

Years later, I’d be able to write the poem I wish my 13 year old self could have articulated …

and while my eyes

have led me down

winding roads, along railways

and onto flights;

too often have I left

my instincts to be educated

by wolves

believing I could

walk on life’s most

turbulent bodies of water

armed with just a

substitute for love.

crashing into darkness.

only to see, the

kaleidoscope of all the love

you’ve given me,

is all I must aspire to be.

This would be my tribute. Thank you!

Mark Anthony Thomas is a writer and creative artist, and has served in executive leadership roles in publishing, communications, and the public sector. Mark Anthony Thomas is the inaugural Fuse Corps Executive Fellow in the City of Los Angeles, serving a 12-month appointment as the Senior Advisor, Livability.