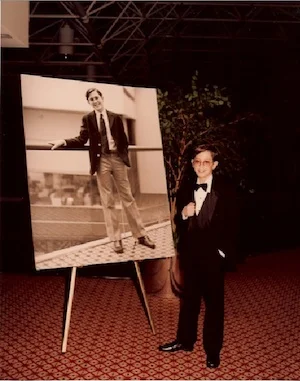

I believe in the Bar Mitzvah. I believe in the idea that — you walk in the door a boy, you ascend this stage, you follow a progression—you risk humiliation, or actually enact humiliation—and you leave something else.

But everything attracts its shadow. We naturally seek safety and we are especially avid in moments of potential danger. There is nothing more dangerous than ritual, and so there is nothing so ossified, so caked over, so drained of feeling and authenticity as the traditional rituals. If there is a single unspoken conviction held by the people who lead them, who watch them, who participate in them, it is this: “You can’t hurt me because I’m not even here.”

So if you ask me, what would I want out of my Bar Mitzvah if I did again, I would say: I want the promise. I want to be a man. I’m still waiting, at 42, to feel like a man. I would like to turn the doorknob and walk into a room and be led through a progression of somethings—and lead a progression of somethings—and turn the doorknob walking out and know that I’ve changed.

But if you ask, what would you want, realistically, I would say: I want to take a risk. And the riskiest thing I can think of in a room of Hollywood Jews is to really talk about God.

* * *

In my late twenties, having pursued psychotherapy and psychopharmacology to the ends of Manhattan, I read William James The Varieties of Religious Experience. In this lecture to skeptics, the skeptical James developed the proposition that regardless of its inherent truth, belief is helpful.

But belief in what? “That there is an unseen order,” James answers, “and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.”

After James, I came to believe in belief. One melodramatically urgent night on the rocks at Big Sur, I actually heard this voice in my head: “The only way out is through God,” except I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now, just what I mean by that word.

The first image that appealed to me was of those three letters as a kind of hyperlink and you press on them and it goes to infinity. This image appealed to me because it suggested that any explication of God whatsoever would be a misconstrual—any part would necessarily be an improper substitute for the whole. In my early yearnings for God consciousness, the priority was not moving toward a good idea but dealing with all the shitty ones. The bearded white man God; the jealous, angry taskmaster God; the stupid God of boundless peace and love.” These ideas of God, it’s like having to sit through The Hangover Part IV and V and VI. But you don’t stop going to the movies because you’ve seen a shitty movie. You don’t give up on God because there are stupid ideas of God.” David Foster Wallace was right: “There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing … is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.”

I spend a lot of time trying to conceive of God, and I haven’t been successful, in part, probably, because thinking is not the right tool. This is so Jewish. Thinking about a problem that is magnified by thought.

But also so Jewish to enact a known tragedy. So I try. When I prayed I felt dead inside so I asked, “Who am I praying to that I feel so dead inside? And I realized that I thought of God like a banker in Boise in a Banana Republic suit—nice guy, wants the best for me, but wouldn’t understand me to the end of the world.

A friend asked me: How would you like to imagine God and I said like a wizened old artist who has made great things and suffered its joys and who really wants me to make great things, too.

Lately, I riff on the idea of God like a fool. I thought the other day. I am riding an emotional roller coaster. And rather than delete this cliché, I extended it. But I’m not going to fall. God is like the lap bar on the roller coaster.

Another cliché. God is not a noun but a verb. God is not the object in the sentence but the active relation between subject and object.

Put another way: It doesn’t matter what you pray to, so long as it’s not you. You can pray to an animal, you can pray to a UFO, you can pray to a record that changed your life. You can pray to a doorknob. You can pray whenever you come into a room—Let me be changed.

Joshua Wolf Shenk is a curator, essayist, and author, most recently, of Powers of Two: Seeking the Essence of Innovation in Creative Pairs (Eamon Dolan Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).