The first time I heard of a Bar Mitzvah I was eleven. And I wasn't invited to it.

If you are a bespectacled, precocious goyishe nebbishe nudnik of eleven with no friends—Jewish or otherwise—you are not invited to the Bar Mitzvah, and, for many years you will have no idea as to what happens in its sacred confines.

Your brother, who is not near-sighted and who has many friends—Jewish and otherwise—will certainly know what a Bar Mitzvah is, because it was just another stop in a whirl of school social gaiety.

If you could not tell by now, my childhood friends were more…observers of social gaiety than partakers of it: Jane Austen, Edith Wharton, Merchant Ivory films and the occasional Vanity Fair Magazine.

Even though we were not Jewish, around when I was eleven or twelve, my mother started to humorously threaten my brothers and I with the prospect of a Bar Mitzvah, because, by her account, it would be the occasion upon which she would throw us out of the house.

The idea was that we would be men, and thus ready to strike out on out own. Understandably, this now gave the concept of a Bar Mitzvah an element of fear entirely different than the one that usually grips thirteen-year-old Jewish hearts.

When I finally did turn thirteen, the only person my mother threw out of the house was my father. With him left my respect for whatever religious establishments had been in my life up to that point: various pastors and ministers who had completely bungled their handling of my parent's separation and eventual divorce.

Alright, so: true story? When I was thirteen, I did not become a Bar Mitzvah. When I was thirteen, I became the son of a single mother and—oddly enough—the recipient of a long-awaited first phrase in Hebrew, courtesy of the Jewish family in our Napa Valley home school group: Hodu ladonai ki tov, ki l'olam chasdo.

Praise God who is good; His kindness endures forever.

In view of the events in my life at that time, the fact that those were the first words in Hebrew I ever learned now seems rather ironic, as there was obviously was lapse in the kindness of God.

Up until that point I had been a fervent believer in God and an avid reader of His oeuvre. I knew the Bible inside and out and, like a good nudnik, I publicly prided myself on my knowledge.

There were characters and narratives from the Bible I knew and loved and adored and projected myself onto endlessly and it is from this period of my life that I would draw my yiddishe nomen—Mordechai—as an ardent lover of that sexy epic of the Jews in exile, Megillas Esther.

In a very oddly disconnected obsession, I was also a fanatic about a musical my mother purchased in a re-mastered double VHS set—

Fiddler on the Roof, because, hello...I was a gay child. Come on. Many gay children have their musical, and mine was Fiddler and yes, I shudder to think of the ones this generation admires, because if you think for even a second that Wicked could hold a Shabbes candle to Fiddler, you're deluded and I have no problem telling you so.

These are facts: I found Topol attractive, but let's not discuss that right now. Chava was my favorite sister. Motl the tailor was the most like me for every reason imaginable, and his name is even Motl, which is the diminutive of my yiddishe nomen, Mordechai.

But, because at that point, I had practically no Jews in my life, I only had the vaguest idea of what it was all about beyond a musical.

That was my childhood.

But I was thirteen now, and though I didn’t have a Bar Mitzvah, my thirteenth year, for what it was worth, was a sort of rite of passage. I knew that God seemed somewhat negligent in his promises and I had to leave the Anatevka of my parent's marriage, my Christian faith and any dearly-held illusions I possessed.

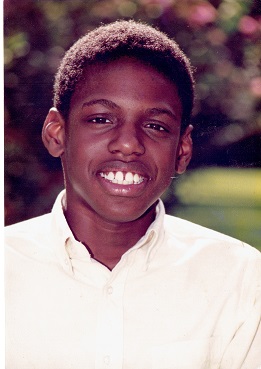

At the tender age of thirteen, I became a fatalist. I held an imaginary cigarette in one hand, a glass of wine in the other and I aspired to be the most creative, educated, erudite and entertaining black person who ever existed in the history of the entire world.

So now imagine I'm twenty-seven and I'm in New York performing in Cosi fan tutte uptown and I'm on a third date with a rabbi who I'm trying desperately to seduce, and in the midst of my seduction I casually let drop that his neck is like a tower of ivory—which you should know is a direct quote from the Song of Songs, which I secretly read like a Playboy when I was eight.

Later on, I give him the big guns: Hodu ladonai ki tov, ki l'olam chasdo--only, it's basically gibberish because no one has corrected my Hebrew pronunciation for fourteen years.

In spite of this, that rabbi is now my fiancé and was the unwitting catalyst for my literal, very real rite of passage into adult Jewish life.

I decided I wanted to return to this literary family of mine that I had acquired as a child: the Abrahams and Issacs and Jacobs and Sarahs and Rebeccas and Rachels and Leahs and Moseses and Aarons, and Davids and Solomons and Mordechais and Esthers of my youth.

Like Ruth, I wanted their god to be my god, so I converted, and the Shabbes after the date of my conversion I had a pseudo Bar Mitzvah at Congregation Sons of Israel in Nyack, New York.

I received my first aliya, gave the dvar torah and sponsored a kiddush luncheon of vegan Chinese food which ran out very quickly. Numerous donations celebrating the event were made to the synagogue in my name, Mordechai Tzvi ben Avraham v'Sarah.

I was a Jew now, and knew that I felt a little more nuanced about my relationship to Hashem and that I had to leave the Anatevka of my formerly goyishe existence for new shores. I held an imaginary khumesh in one hand, a tumbler of Manischewitz in the other and aspired to be the most creative, educated, erudite and entertaining black person who ever existed in the history of Judaism...but that's another story for another time.

Eventually, my fiance and I moved to California, where we joined a shul in Berkeley, and after a couple of years, totally out of the blue, I was asked if I wanted to be an educator in the B'nei Mitzvah program.

And I said no, like, a thousand times--how could I? I hadn't even had a Bar Mitzvah myself! But here's the thing: how many generations of Jewish women assisted in the education of Jewish boys for a religious life they could not themselves pursue? Did they let this stop them?

No, and neither could I.

Unlike these generations of strong Jewish women, however, I taught myself how to read trope using an app. Then I made a series of videos with another app using internet pictures of cats to teach children what I had taught myself.

And a couple of weeks ago, I just leyned Torah for the first time at the Bat Mitzvah of one of my students.

Someday--when I am not too busy assisting children with theirs--I will have a real adult Bar Mitzvah, or as I will term it in the euphonious Ashkenazi accent, a Bar Mitsve.

It will be a portion that has immense meaning for me. My family will be there, especially my brother.

I will attempt to do every Torah reading and the Haftorah reading as well. They will be read in the Asheknazi accent, the accent I heard from old Jews in New York when I first started attending shul, the accent of the Ashkenazi Jews for one thousand years.

I will give a d'var Torah and Chassidic lore pertaining to the portion will be discussed. There will be a decent kiddush luncheon, and a tish on Havdole. Veretski Pass will play and Bruce Bierman will lead the dancing. There will be none of this sloppy "I've been to a few Bar Mitzvahs and I'll guess I'll dance"-type dancing.

There will be singing--real singing-- and drinking--real drinking--and dancing--real dancing.

A singer of Yiddish and cantorial music and creator of “Convergence,” a multi-media blend of Yiddish and Hebrew songs with African-American spirituals.