In the spring of 1981, with an August Bar Mitzvah rolling inexorably in my direction, I was obsessed with two things: The angle of my hair, and the question of whether I might be a tzaddik.

The first one is easier to understand. I was 13, the girls in my class all loved Parker Stevenson’s blow-dried hair (the real star of the Hardy Boys TV show), and I was saddled with a helmet of impractical locks that defied gravity, the curls above my ears pointing sideways like the Steve Martin arrow-through-the-head posters gracing the bedrooms. As I sat in Hebrew school I shuddered to think about being up on the bima, my curls levitating and separating as I sat on the oversized chair next to the rabbi, imagining my friends imagining me being Steve Martinized. I wanted to take the yad and stick it through my ears, ending the horror.

The second one became a thing during one of my Thursday afternoon follicle-hating reveries, when I was invited into the rabbi’s office to talk about the obligations and responsibilities of the upcoming event. Our rabbi was a quiet mystic, with an otherworldly authority. On this day there was no dispensing of stale Stella D’oro cookies, as he launched right into The Story:

“The Kabbalists taught that in every generation there are 36 tzadikkim, holy souls, whose existence maintains the heartbeat of the world. Without the good deeds of each and every one of them, without their iron-clad commitment to tzedakkah, the world would collapse in on itself. These tzadikkim, called lamed-vavniks – the Hebrew term for the number 36 – do not know who they are. You are a good boy; a very good boy, in fact. You do tzedakkah like you mean it. And when you are up on the bima, I know you will think about the lineage that the thoughtful among us hope to join.”

At first I was grateful for this advice, as it gave me something else to think about when I imagined being on the bima. While my pubescent co-religionists would pretend to put an arrow through their brain, mocking the rebellion of my hair, I would be reflecting on the moral courage of my ancestors, and considering the club I might join if I continued being the "very good boy” I just had been anointed.

But gratefulness soon turned to terror. For four long months I impaled myself on the first philosophical question that had ever grabbed me by the throat: How can I do the work of a lamed-vavnik if I am arrogant enough to consider myself one? Is that not an unsolvable paradox?

So night after night I sat in my room, picking over this argument in my mind, vaguely aware that I had begun to engage in the kind of Talmudic hair-splitting associated with my forefathers. If I believe I am a lamed-vavnik, I said, I can’t be one; a lamed-vavnik can’t know that’s who he is, and wouldn’t allow himself to be distracted by that question. Even asking the question might poison my good deeds, as each deed might be done in part to try to ascertain whether or not I could be deserving of such an accolade. In order to do holy work, therefore, I must distract myself with thoughts about doing unholy work.

Eventually the emotional logic of a narcissistic teenager took me full circle: In order to be considered a candidate for lamed-vavnik-hood, I needed to focus on something non-vavniky, which in my case was a fairly obvious subject: My hair.

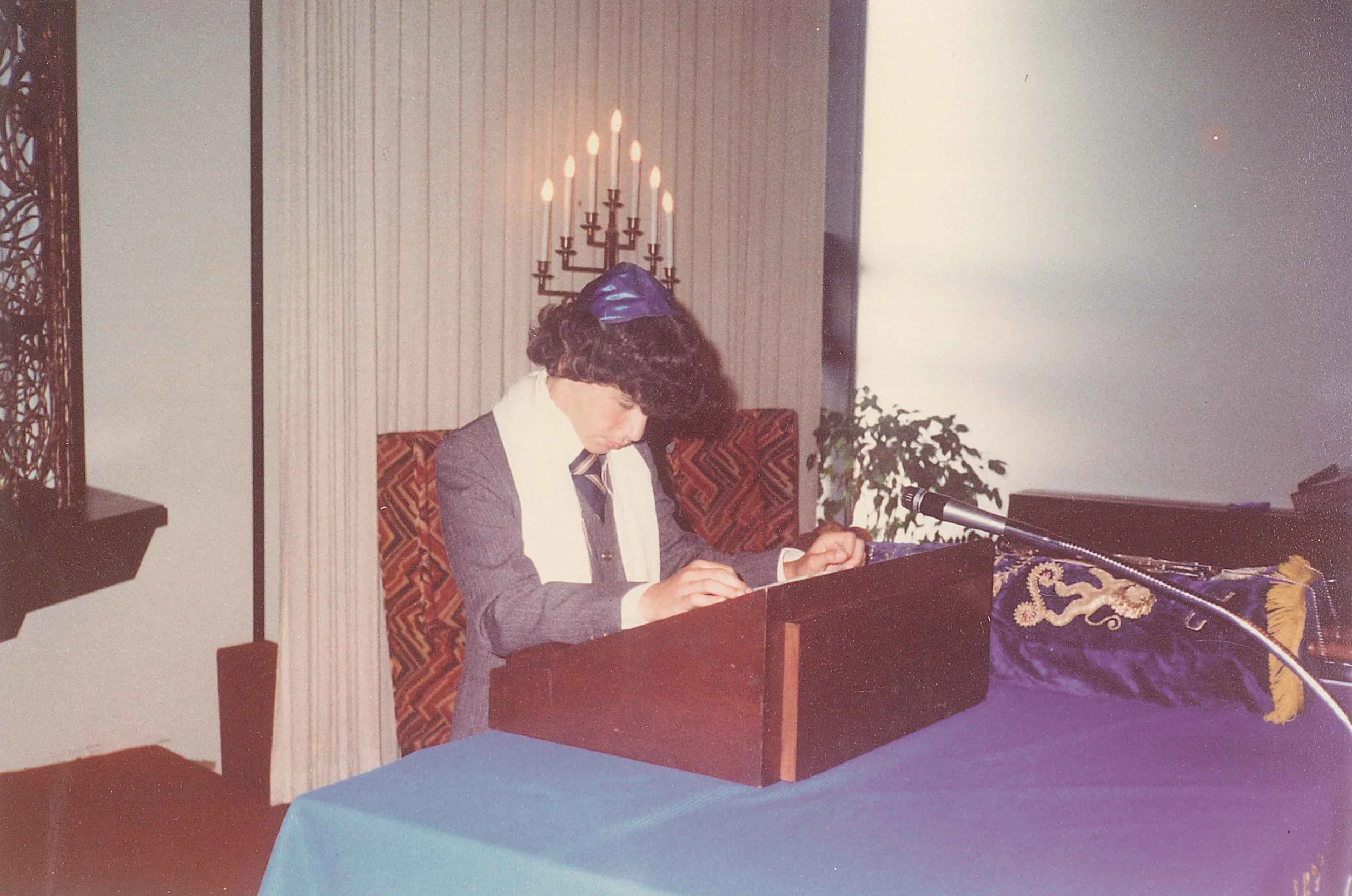

And so on a warm August morning, vacillating between rehearsing the Torah trope and patting down my curls, I wandered into the sanctuary. I was fairly sure I could execute my Torah assignment with competence, but unsure how present I could be given the vavnik-noises in my head.

“Your hair looks great,” one of the girls said as I fiddled with the buttons of my blazer. With a spring in my step I ascended the bima, and for the first time in my shy life my hair and my emotions, how I looked and how I felt, were in synch.

You want to know the Jewish moral of this story? How these events shaped the Jewish man, the Jewish writer, I became? For 34 years I have told stories and tried to heal the world. I have puffed myself up and tore myself down, and cycled through months of agitated reflection and singular moments of peace. Through all this I began to understand the rough justice of Jewish rituals. For the sense of peace and satisfaction that attend to the center of the Jewish ritual experience, one must do the hard work, ask the hard questions, convolute oneself with doubts. And then one must allow oneself the accidental grace of looking on the outside as good as you feel on the inside.

The ancient priests were required to look immaculate, a vision of rightness intended to evoke the suitability within. To look good and act well, to be allowed to live fully and unselfconsciously inside our primal Jewish rituals, is a gift. Even during our ironic, post-modern, 21st century Jewish lives.

Daniel Schifrin’s fiction and essays have appeared in McSweeney’s, the Los Angeles Times and the San Francisco Chronicle, and he has finished a novel and short story collection about Jews making terrible mistakes.