Blame it on Great Neck.

Great Neck, Long Island.

The Bat-Mitzvah Mecca.

My public-school -teacher parent’s… worst nightmare.

It’s 1983. I’m at Robin Silverstein’s Bat- Mitzvah. Robin spelled with an “i”, not to be confused with the Robyn spelled with a “y”.

I’m wearing a Gunney -Sax white princess dress, lavender Chinese slippers and Maybelline’s Frosted Brownie lipstick. It looks like I just took a bite into a powdered donut …or did a big 8 ball of blow.

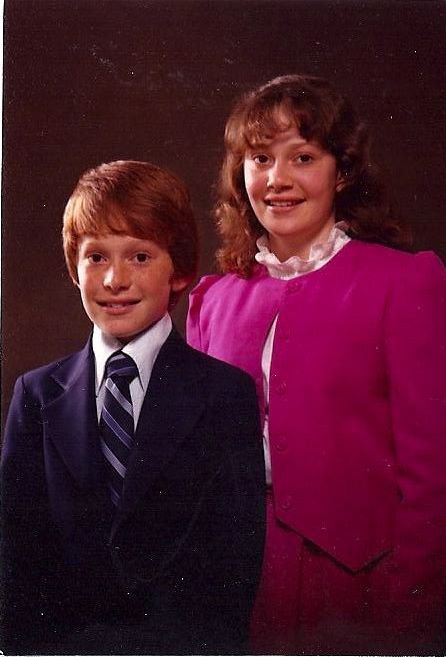

My father drove me here and bitched about the traffic the whole way up. He is distressed that I now have so many friends in Long Island. But he sent me to Jewish Y sleep away camp, and there are only two of us from New York City. I don’t think it’s fair that Long Islander’s call themselves New Yorkers. Great Neck is very clean. They have pink stores that sell big rainbow pillows, and stickers. I love stickers. I have a sticker collection, in a photo album. Stickers of ice cream sundaes, unicorns, hearts and ballet slippers. My friend Josh Walberg says sticker collections are “JAPPY.” You don’t ever want to be called a J.A.P. I’m more of a roller disco queen. I try to walk the J.A.P. walk, but my mother refuses to pay for an alligator sewn on a shirt, when the one with a tiger is cheaper. So I get “LE TIGRE” shirts from WINGS on 96th and Broadway. I like them best when they still have the creases from the cardboard folder. I’m also too chubby for Guess Jeans, which is probably for the best because my mother says they are nothing but overpriced jeans with a triangle on the tush. I wear corduroys called “Prime Cuts”, because they have elastic around the waist, and as mom says “they’re roomy on the thighs”.

I want to like camp but I hate it. Being fat in the NY public school system is one thing, but being fat in Jewish Y Sleep away Camp is a mini death wish.

I’m a popular fat girl. Which means I’m friends with all the prettiest girls, and all the guys are best friends. The boys want to consult with me day and night. They all talk to me about my girlfriend’s that they like. I’m like a little teenage therapist.

My mother says I’m very verbal. One time I was talking so much that a bee flew straight into my mouth, and stung me right inside my cheek. When I was five my father tried to get me into this alternative public school for smart kids. I scored incredibly high on the verbal section, especially when I told the lady she was a “riot”. “You’re a riot,” I kept saying, “You’re a riot!” And then I blew her away when I mentioned her blouse was “absolutely stunning”, which she thought was a very mature compliment for a five year old. My mother was beaming. But when it came to the logic section, I had a short circuit breakdown. They had me fitting shaped blocks into their congruent slots. I kept trying to squeeze the triangle into the circle. They carried me out screaming, chubby fists wielding, and told my parents I was severely undeveloped in the right side of my brain. So my dad bought me this funky fractions game in the shape of an apple pie. It just made me want to eat pie.

Robin Silverstein has a lot to live up to with her Bat-Mitzvah. Cause Sharon Goldfarb’s had invitations that unfolded into life size posters of Tom Selleck. Also, Sharon’s dad owned like all of Broadway, so he got the cast of “Cats” to come out of garbage cans on the dance floor. But I heard he got pissed cause one of the “Cats” was smoking a cigarette outside after the party, and everyone saw, and he thought that ruined the “magic.” I began fantasizing about what cool famous people & gift bag swag, my parents could arrange for my party. They only brought home teachers with channel 13 tote bags, number 2 pencils and half fare bus passes.

Robin ended up hiring the New York City break-dancers for her Bat- Mitzvah. This felt like a big rip off because two of the dancers went to my school, so I get to see them dance for free all the time! She also had a reggae band, and the band guy was annoyed because Robin kept making him sing her favorite Phil Collin’s song. “I can feel it coming in the air tonight.” Then they had a drumroll and the band guy said, “Hereeeeeee’s the Silverstein’s.” And the Silversteins came out on the dance floor enveloped in a flooding spotlight, arms linked in gowns and suits.

On the drive home my dad kept muttering that the Silverstein’s spotlight entrance was “excessive.” I thought it was awesome. I liked that Robin was placed in the middle. My parents were divorced and probably wouldn’t want to link arms.

But hands down, the most CRIMINAL thing about Robin’s Bat Mitzvah was that she didn’t even have to go to Hebrew School to earn it. I had to go THREE times a week since the third grade, and learn how to read my Torah section IN HEBREW!!! Robin went to a crash course called “Quick Bat” where they wrote out her Torah section in English letters. How unfair is that!

The summer before my Bat- Mitzvah my mother sat me down and broke the news that my Bat- Mitzvah party was going to be…(drumroll please) in our apartment. You’d think she was telling me, the family cat had died. She explained to me that the Greatneck Bat- Mitzvah’s were outlandish, bordering on “obscene.” I never heard her use that word before and it sounded… scary.

“Oh my God. Can I even get invitations made???” I panicked.

“Yes, we will get some nice invitations. But they can cost no more than the price of a regular postage stamp.”

Welp. This was just great. Scratch my idea of invitations unfolding into Michael Jackson with his pet llama Louis.

My mom looked tired. She assured me it was going to be a very nice party and that we have a beautiful apt. She mumbled something about go complain to your father, and reminded me of how nice my sister’s party in the apartment was.

“ Is there going to be a band?” I knew the answer. No.

“Photo booth?” Nope.

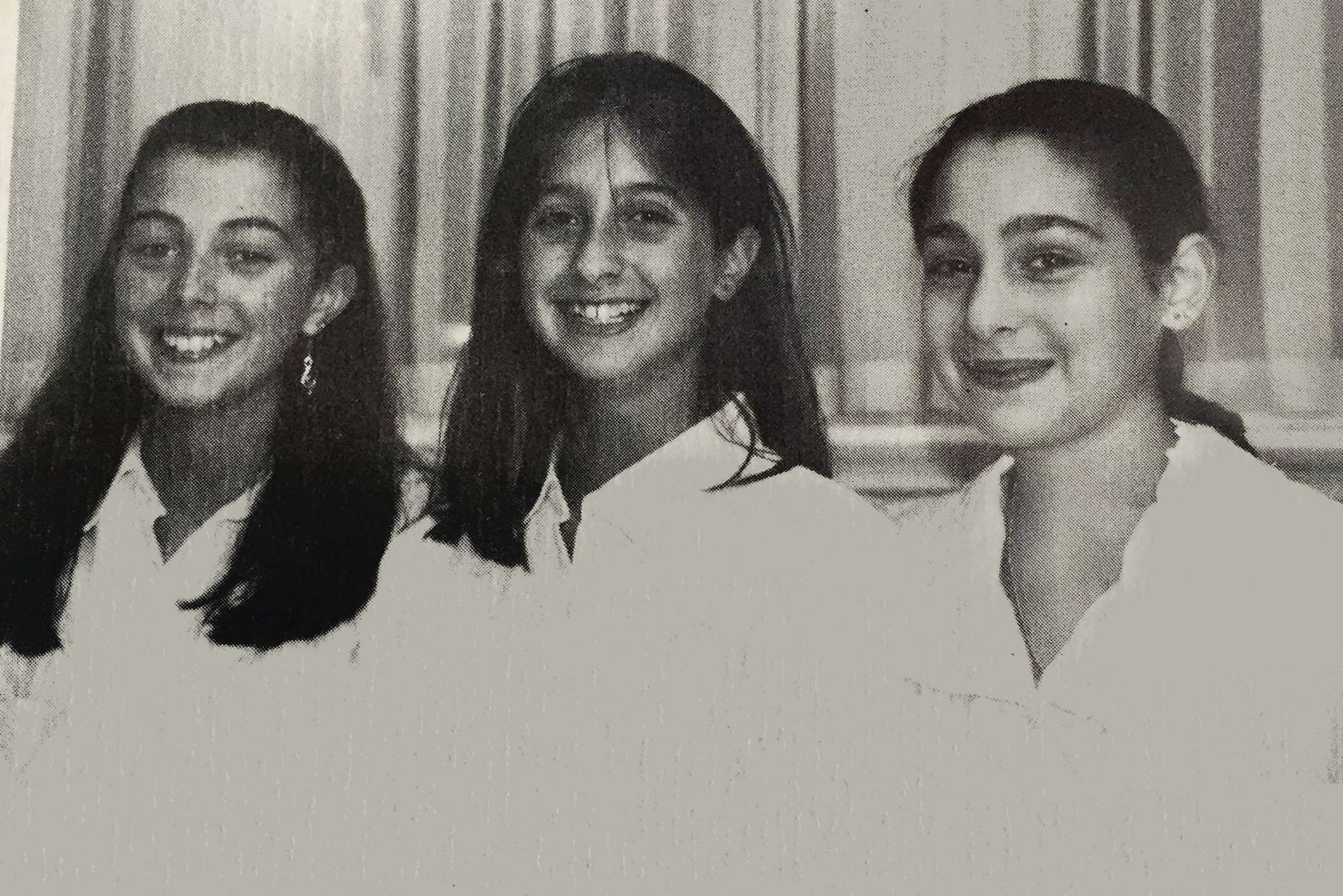

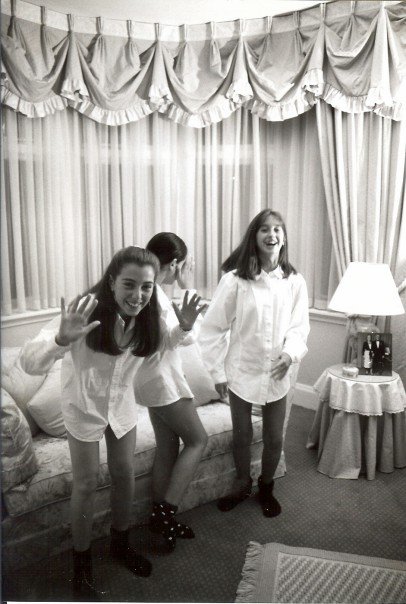

“But.. You can have a special kids after party in the living room after the adults leave.”

Yes. I liked this.

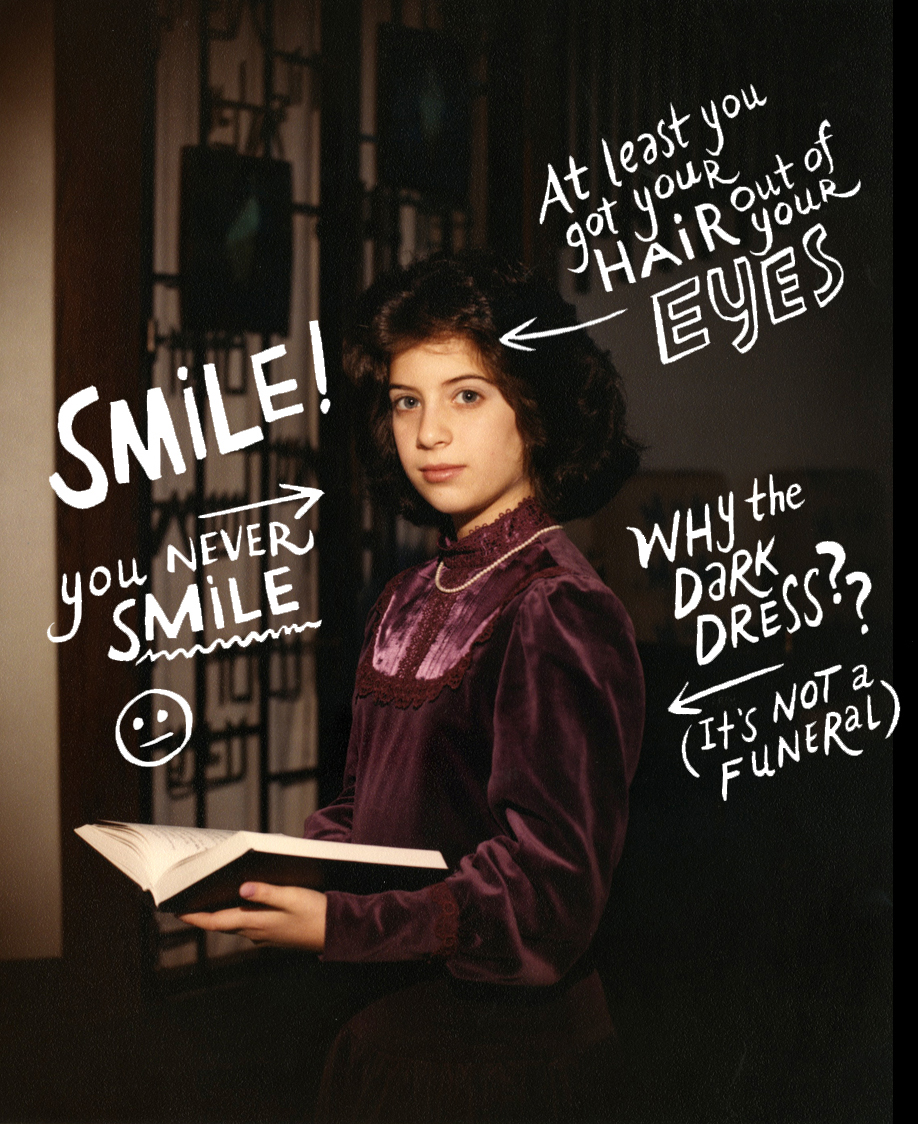

“And we will go to Alexander’s and find a Gunney Sax dress.”

Deal.

Over the next few weeks I kept hearing my mother use the word “modest” on the phone with her friends, to describe my upcoming Bat- Mitzvah. I wasn’t quite sure what that meant by that but I forgoed asking her to come out with my dad in the spotlight.

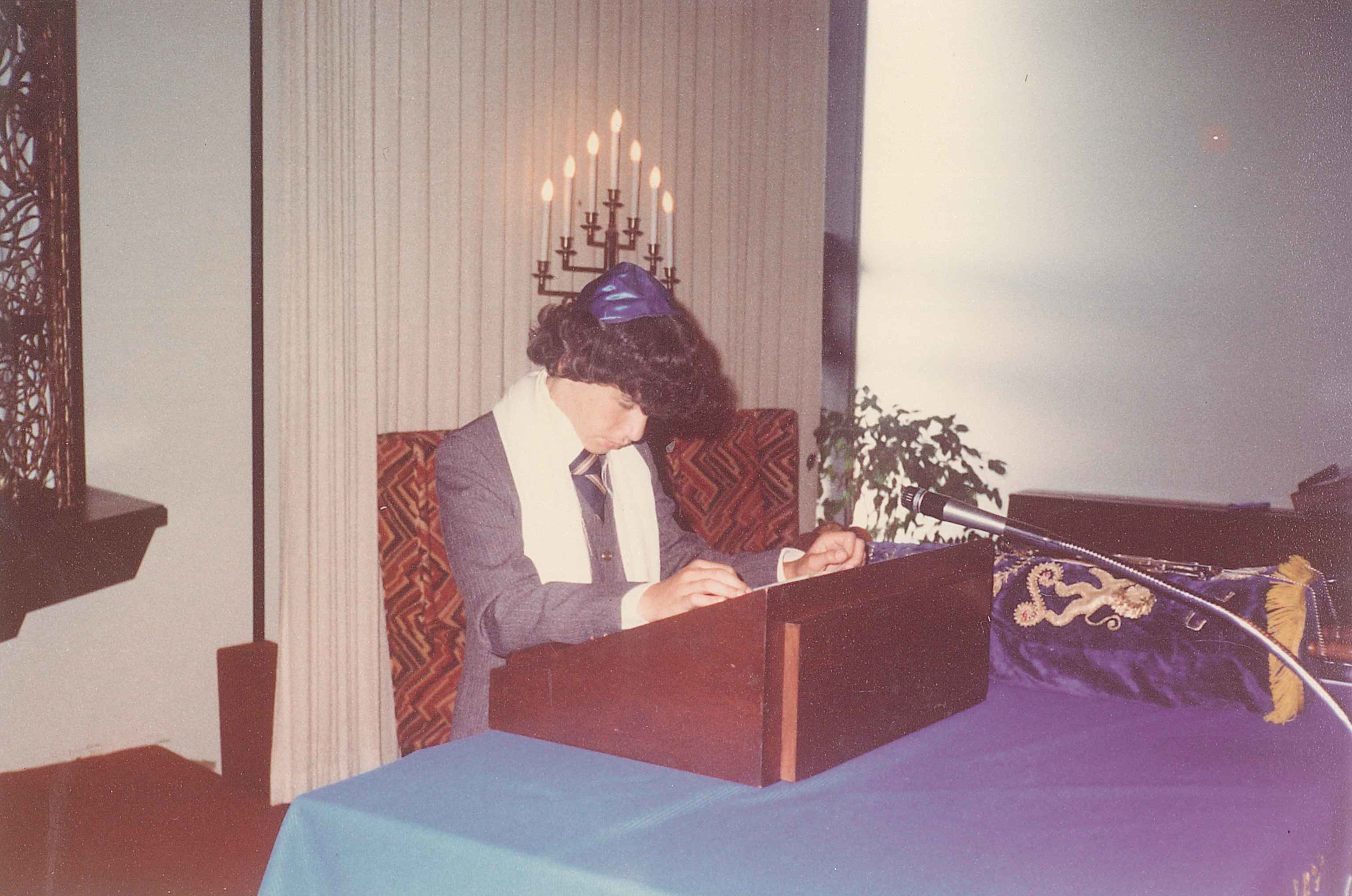

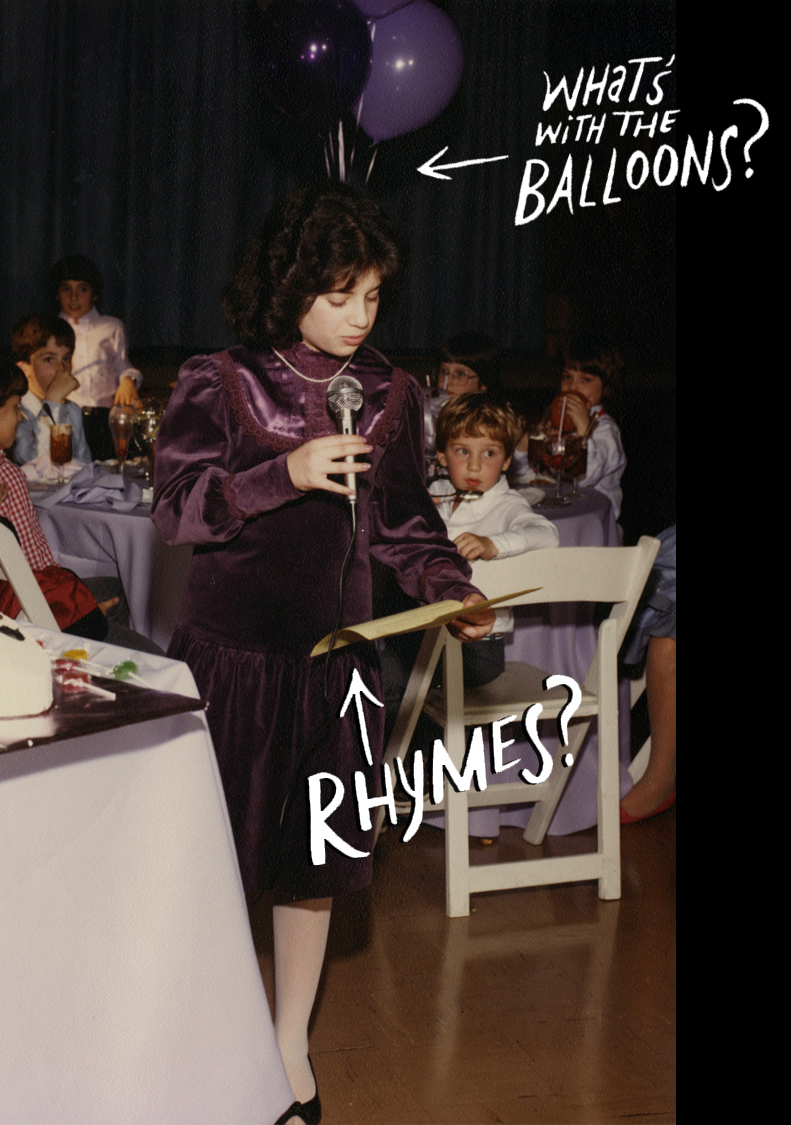

All fall, I practiced my Haftorah portion with my little Casio tape recorder. Cantor Kornreich made little notations on my script as to when my voice should go up and down. I had just gotten the role of Princess Leah in the Hebrew School musical Production of “The Empire Chicken Strikes Back” so I was feeling a little cocky. “Darth Veys Mir” and I were quite a team up there.

I barely remember my 15 minutes of Bima fame, but I remember being proud all my hard work paid off. I remember everyone thinking the after party was really cool.

I eventually lost touch with my Greatneck Friends. My father got tired of driving me out there, and well.. Let’s be real, I never really fit in.

I’m forever grateful that I now understand what “modest” and “obscene” mean. I see my sister teaching her children down to earth values like we had. They understand that getting a manicure is a treat, and that homemade birthday cakes are better than store bought.

Today I have a tinge of guilt that I was so affected by my Bat Mitzvah Mecca phase, but I’m grateful my mother put her foot down, and gave me everything a public school, right brain deficient, chubby teenage therapist needed.

Spoken Word Artist/ Author/Actress/ Native New Yorker Vanessa Hidary began her spoken word career at the legendary Nuyorican Poets café. She has aired three times on “Russell Simmons Presents ‘Def Poetry Jam’ on HBO. She was featured in the short film "The Tribe", SummerStage NYC, and was chosen as one of 50 speakers to appear at the “2010 IdeaCity- Canada's Premiere Meeting of the Minds'” She lives in Manhattan, where she published her first collection of poems and stories titled “The Last Kaiser Roll in the Bodega.” She is currently producing and directing a showcase called KALEIDOSCOPE which explores ethnic and racial diversity within The Jewish community.